Duty and Humanity

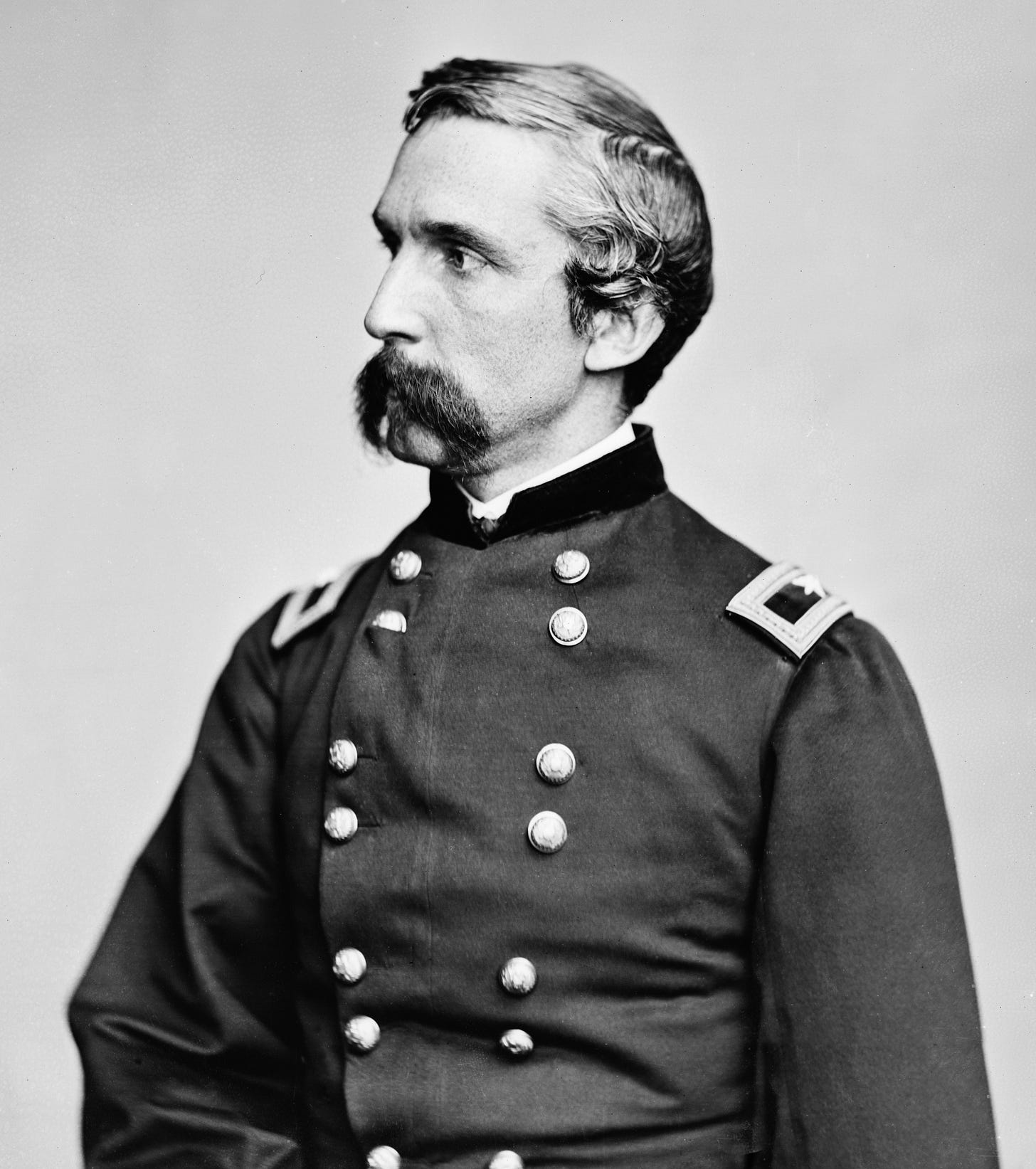

The Transformation of Joshua Chamberlain from Scholar to Leader

The weight of unread Homeric epics sat heavy on Joshua Chamberlain's desk. A professor of languages at Bowdoin College in Maine, Chamberlain's life revolved around the dusty wisdom of the past. Yet, the year was 1861, and the thunder of a nation tearing itself apart echoed far louder than the whispers of ancient Greece.

Chamberlain, a 33-year-old man of quiet but unwavering conviction, couldn't reconcile deferment with duty. He wrote to Maine’s governor, “I fear this war, so costly of blood and treasure, will not cease until men of the North are willing to leave good positions, and sacrifice the dearest personal interests, to rescue our country from desolation, and defend the national existence against treachery.”

Granted leave from Bowdoin to study in Europe, he secretly enlisted in the military. He didn’t even inform his wife and two children beforehand. Soon, he found himself Colonel of the newly formed 20th Maine, a ragtag group of farmers and lumberjacks. Chamberlain, with his scholarly background, might have seemed an unlikely leader. But his genuine respect for his men, combined with a tactical mind honed by years of studying historic battles, fostered an unshakeable bond.

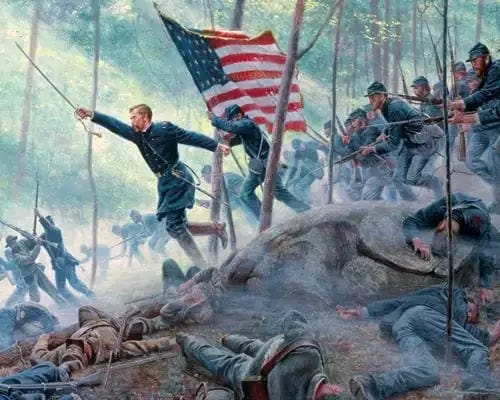

The crucible of Gettysburg arrived in July 1863. On the second day of the battle, the 20th Maine occupied Little Round Top, a seemingly insignificant rise of ground. Yet, the Confederates, recognizing its strategic value, launched a relentless assault. Under withering fire, ammunition dwindling, the 20th nearly folded back on itself, the left side of the line facing southeast while the right faced west. Chamberlain made a decision that would etch his name in history.

“At that crisis, I ordered the bayonet. The word was enough,” Chamberlain wrote in his battle report.

A wave of steel against a storm of lead, the 20th Maine surprised the flanking Confederates, driving them back down the slope. This desperate fight secured the Union position and arguably saved the entire flank.

Victory, however, brought no revelry for Chamberlain. War's brutality had etched itself onto his soul. When fate placed him at Appomattox Court House, tasked with receiving the Confederate surrender, Chamberlain refused celebratory fanfare. He ordered his men to come to attention and “carry arms,” a gesture of respect for defeated foes.

In his memoirs, Chamberlain wrote:

“Gordon [the surrendering Confederate general], at the head of the marching column, outdoes us in courtesy. He was riding with downcast eyes and more than pensive look; but at this clatter of arms he raises his eyes and instantly catching the significance, wheels his horse with that superb grace of which he is master, drops the point of his sword to his stirrup, gives a command, at which the great Confederate ensign following him is dipped and his decimated brigades, as they reach our right, respond to the ‘carry.’ All the while on our part not a sound of trumpet or drum, not a cheer, nor a word nor motion of man, but awful stillness as if it were the passing of the dead.”

In that quiet moment, Chamberlain embodied the spirit of reconciliation, a testament to the humanity that could still flicker even amidst the ashes of war.

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain returned home a hero, but the hero he truly was transcended battlefield glory. He was a scholar-soldier, a leader who understood the cost of war but never lost sight of compassion. He continued on to be governor of Maine, president of the college he once left to go to war, and commander of the Maine Militia, once facing down armed men in the state capitol.

His story serves as a reminder that courage can bloom in the most unexpected places, and that true victory sometimes lies in the quiet dignity of a simple act of respect.

Learn more about Chamberlain:

Jeff Daniels depicts Joshua Chamberlain in the 1993 movie ‘Gettysburg’ based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Killer Angels” by Michael Shaara.

Ronald C. White has written a biography on Chamberlain named “On Great Fields.”

“The Last Salute of The Army of Northern Virginia” written in 1901 with excerpts from Chamberlain’s personal memoir.