From Protest Comes Prosperity

The Bonus Army and the Birth of the GI Bill

The year is 1932. America is in the throes of the Great Depression. Thousands of World War I veterans, promised a bonus for their service, see their dreams of financial security vanish amidst breadlines and unemployment.

World War I veterans returned home expecting a hero's welcome and a brighter future. Instead, they soon found themselves thrust into a harsh reality. Jobs were scarce, the skills they honed on the battlefield didn't translate well to civilian life, and the promised “bonus payment” for their service seemed like a distant dream – not due until 1945. The economic boom that followed the war fizzled out quickly, leaving many veterans financially strapped. Adding to their woes, the psychological scars of war, then known as “shell shock,” were widespread, with little support available for veterans grappling with depression, anxiety, and nightmares.

The government's lack of assistance stood in stark contrast to the enthusiastic wartime calls to patriotism. The public, too, began to question the government's commitment to the men who had served. By 1932, the Great Depression had piled onto the existing hardships, pushing many WWI veterans to the brink of destitution.

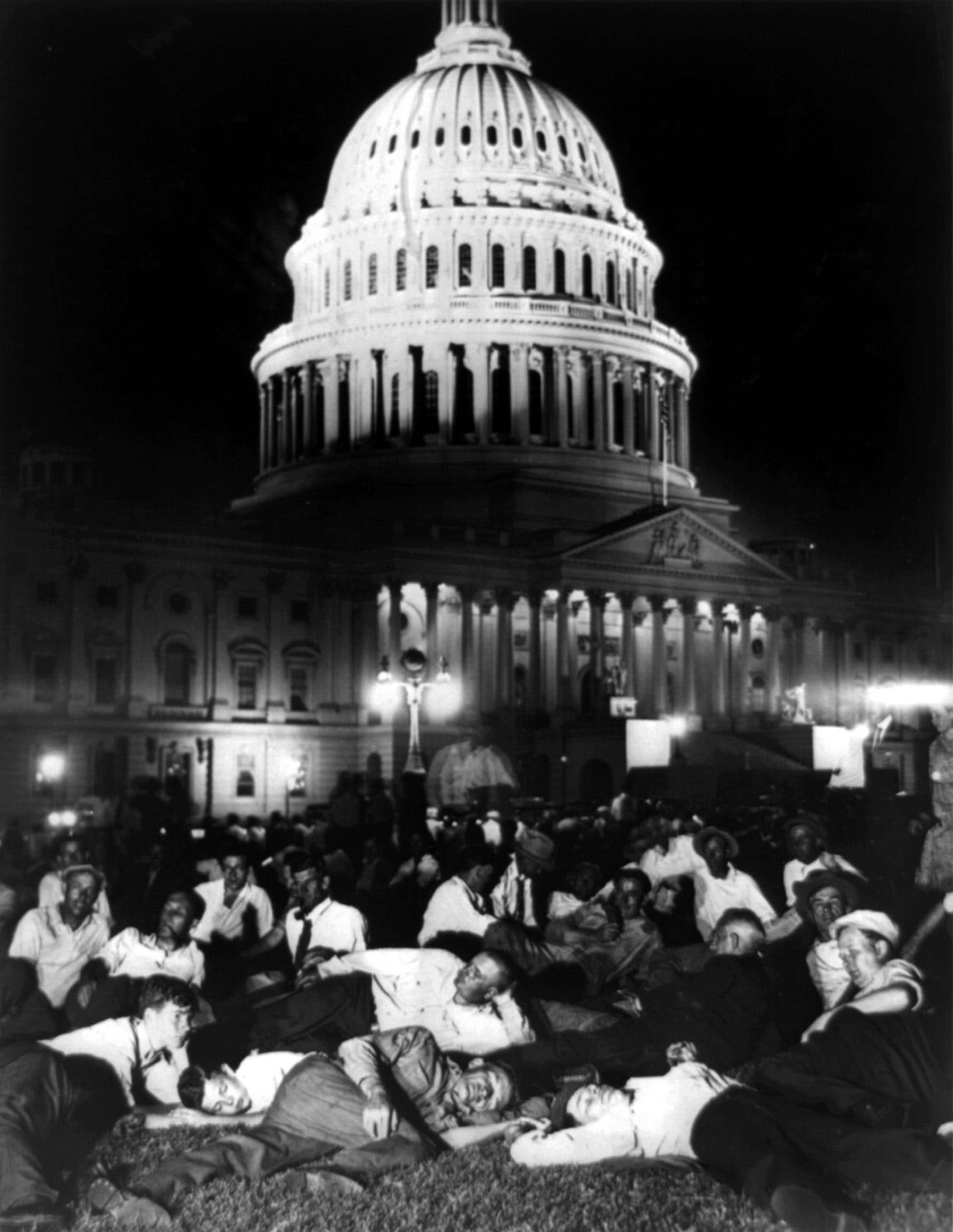

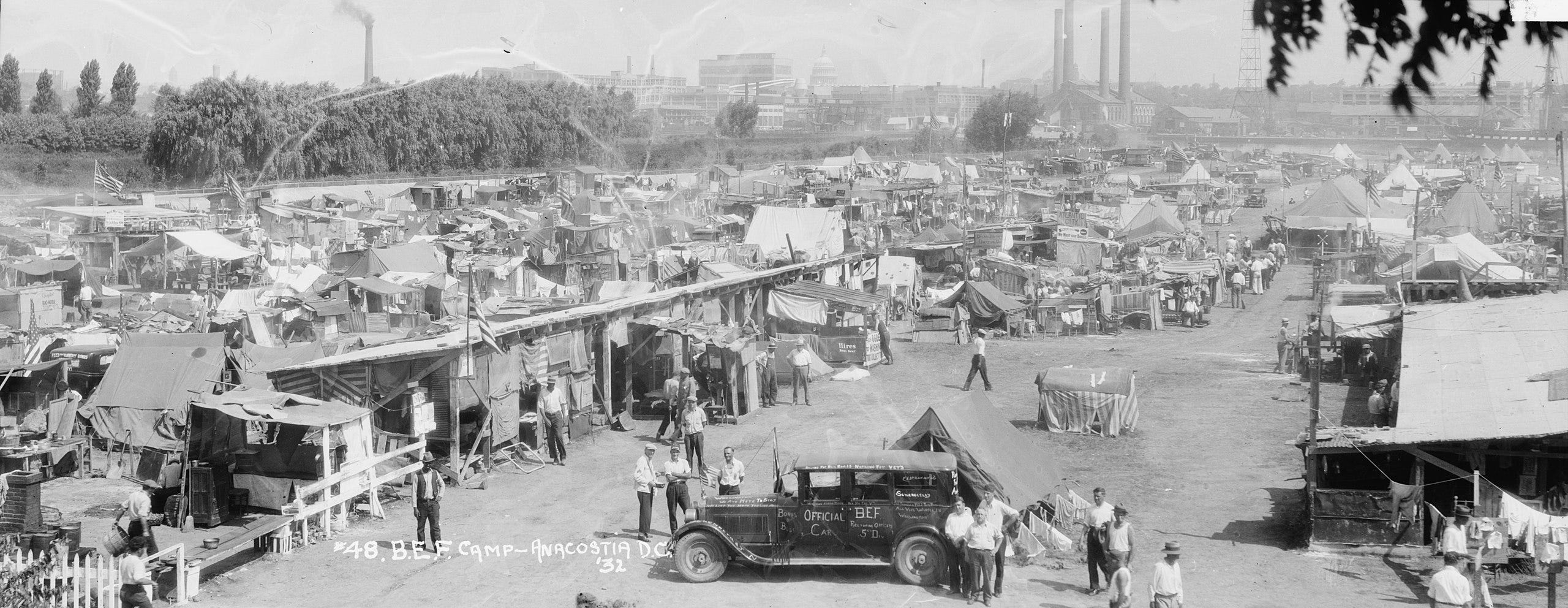

Desperate for financial relief, 17,000 veterans, along with their families and other supporters, descended on Washington D.C. in June. This became known as the Bonus Army in the media of the day, but the group called themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force. After initially being rebuffed by President Herbert Hoover and the Senate, many of the veterans who had homes returned to them. However, many thousands had nowhere to go, and so they stayed in D.C., and many more thousands arrived to join them.

They camped out in several makeshift shantytowns, their plight capturing national attention and highlighting the government's neglect. One camp was nicknamed “Camp Marks” after a local, friendly police captain. Another was named “Camp Bartlett” for the man who owned the land and permitted the veterans to camp there. The camps were organized and policed by the veterans. They did their best to make sure residents were honorably-discharged veterans and their families, trying to protest legally for their bonus. They reportedly ran out criminals, Communists, and other people not dedicated to their cause. They also organized church services, first aid tents and sanitation regimes. The racial segregation that had held strong, even on the WWI battlefields, began to melt away within the camps. Food was provided by supporters with assistance from the local police, whose chief was a WWI veteran himself.

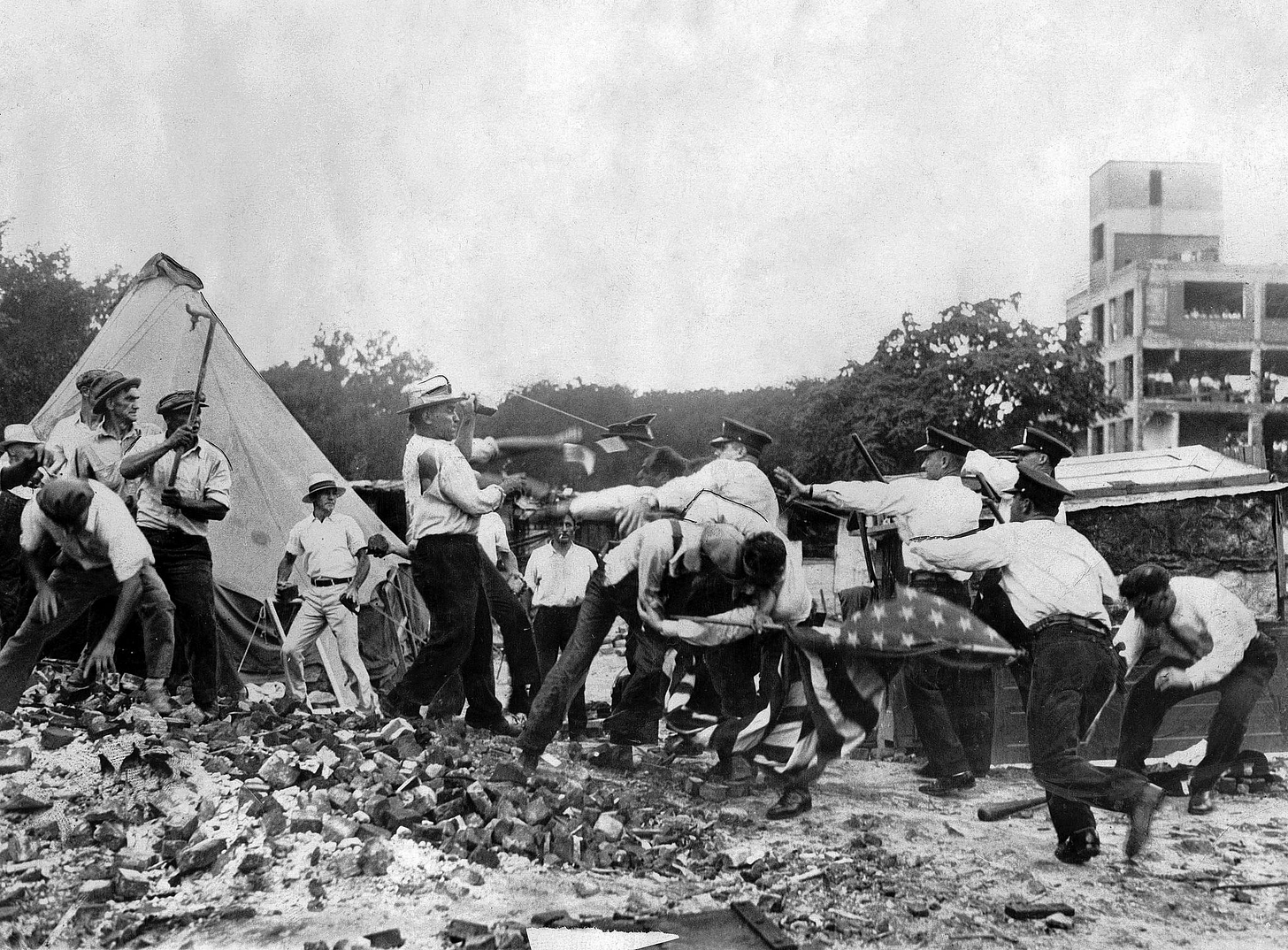

But the D.C. Commissioners, under prodding from Hoover, had enough of the protest by late July. They felt the Bonus Army was bent on revolution, a threat to national security, and dangerous for the city. On July 28, the Commissioners ordered the police to remove the Bonus Army from partially-demolished, publicly-owned buildings they had occupied inside the city. Bonus Army leaders urged veterans to go peacefully, but some veterans rioted against the officers, leading one to draw his service revolver and shoot into the crowd. Two veterans later died from the gunshot wounds.

That afternoon, President Hoover used the violence as his reason to authorize the Army to move in against the veterans. General Douglas MacArthur, eager to quell what he saw as a revolutionary army, led a force consisting of the 12th Infantry, the 3rd Cavalry (led by George Patton), and a handful of tanks to clear the protestors. As the troops amassed, the veterans believed it was to be a march in their support, and began cheering on the uniformed soldiers. But then bayonets were ordered to be fixed, cavalry sabers drawn, gas masks donned, and the troops ordered to advance on the gathered veterans.

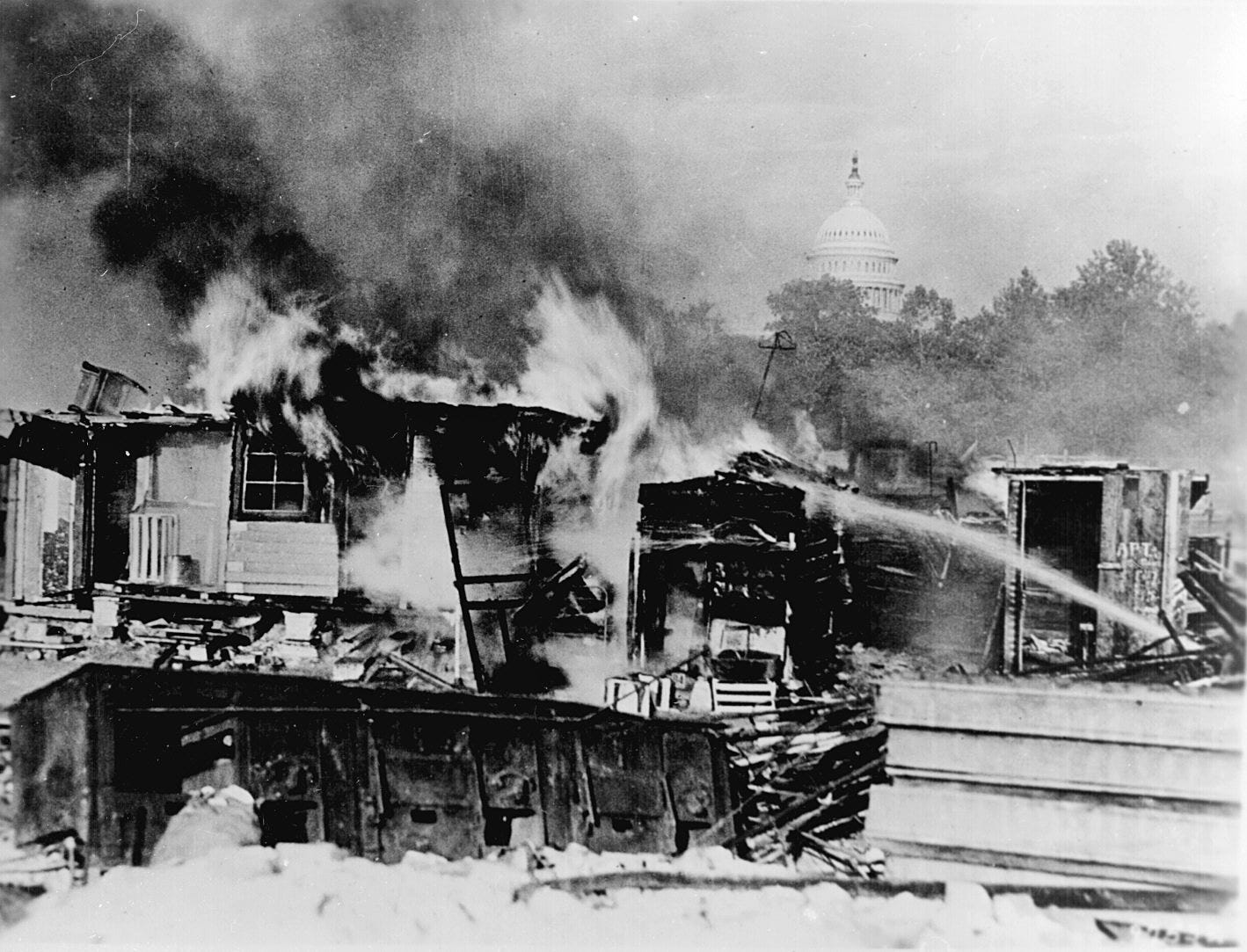

The veterans were driven south across the Anacostia River by prodding blades and tear gas to the large camp at Anacostia Flats. The camp there was on private property, they believed they would be safe there. Hoover issued orders for the Army not to cross the river, but MacArthur, choosing to ignore the order, initiated a further attack and wiped out the larger camp as well. The camp was burned to the ground. Who set the blaze is disputed.

No deaths were reported, but many injuries. Thousands of veterans, many with their families, had nowhere to return to. They were made into refugees in their own country, by their own government. They left D.C. for cities across the country to stand in breadlines, a reminder to everyone of what had happened on July 28.

Hoover and MacArthur accused the bulk of the protestors of being Communists and revolutionaries, and that fewer than 10% of them were actually WWI veterans. But the image of the government clashing with veterans sparked public outrage. These veterans, having fought for their country, were now facing homelessness, economic despair, and violence at the hands of the government they had fought to support. Their plight resonated deeply with a nation grappling with its own economic woes. Policymakers, including a young Franklin D. Roosevelt, took notice. He would be swept to victory over Hoover during the next election in part due to the outcome the protest.

Fast forward to 1944. World War II rages on, but America has learned a harsh lesson. Roosevelt signs the Servicemen's Readjustment Act, better known as the GI Bill. This landmark legislation went far beyond a simple bonus. It offered returning WWII veterans a pathway to a brighter future, with education and homeownership at its core.

The GI Bill's home loan program, with its low-interest rates, proved to be a game-changer. Veterans, with stable jobs and financial backing, could finally achieve the American dream of owning a home. This wasn't just about individual prosperity; it fueled a national housing boom and the creation of a highly-skilled workforce. Suburbs sprung up across the country, creating construction jobs. Home ownership fostered a sense of community. The GI Bill, born from the ashes of the Bonus Army's protest, became a cornerstone of the post-war economic boom and the rise of a robust middle class.

However, it's crucial to acknowledge the GI Bill's limitations. Discriminatory lending practices, often referred to as redlining, denied many minority veterans the opportunity to fully participate in the housing boom. This remains a permanent stain on the program's legacy.

The story of the Bonus Army and the GI Bill is a testament to the power of collective action and the ability to learn from past mistakes. It's a powerful reminder that investing in veterans isn't just the right thing to do – it's a recipe for national prosperity. The Bonus Army’s fight for recognition may not have been a victory in the moment, but their courage and sacrifice paved the way for a brighter future for veterans to come.