Not Forgotten

How science brought two more heroes home after decades

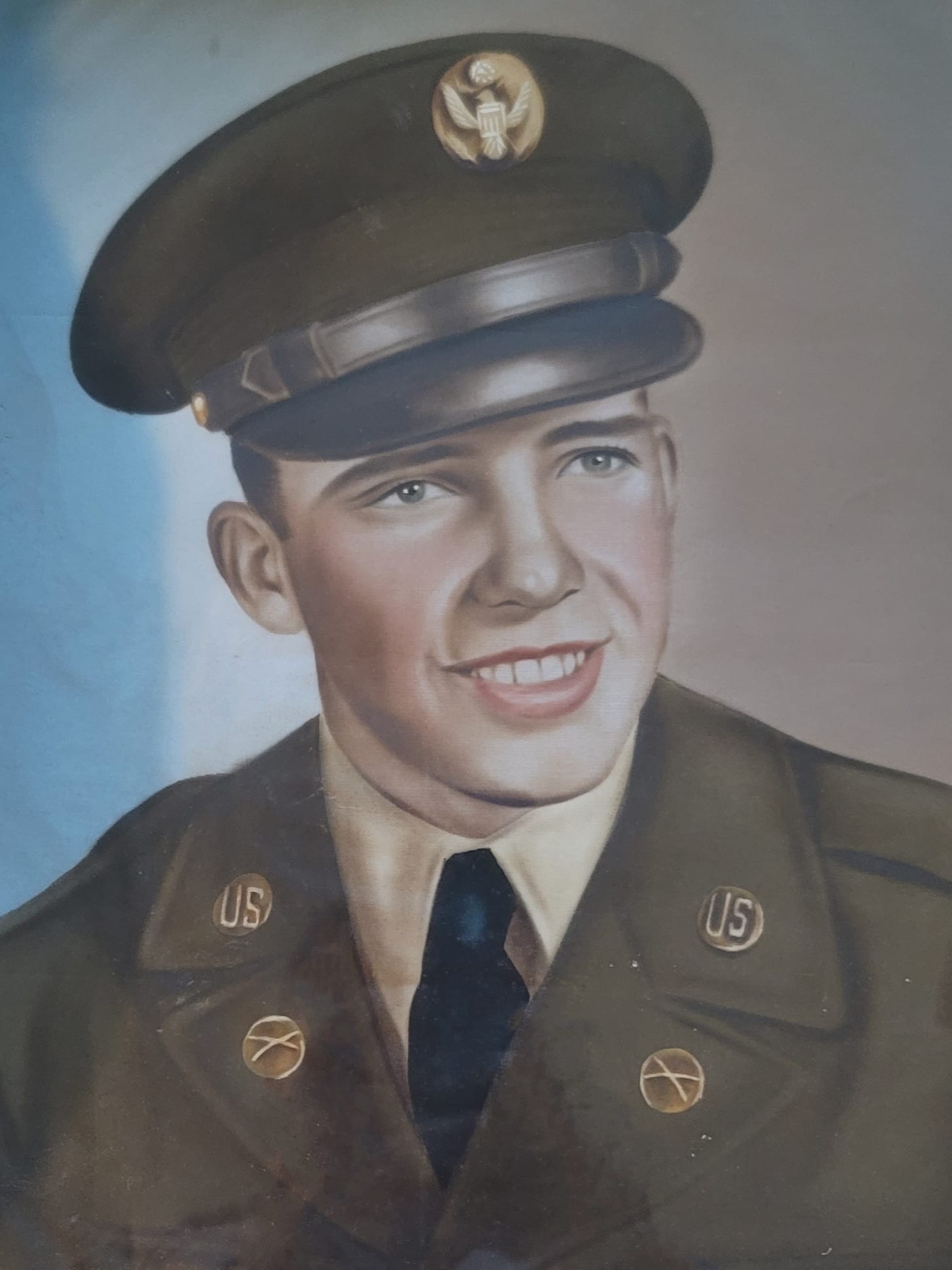

On a winter night in 1950, Private First Class Arthur A. Clifton disappeared into the frozen chaos of the Chosin Reservoir.

Thousands of miles and decades earlier, in the cold air over Germany in 1944, Staff Sergeant Yuen Hop’s final mission ended in fire and wreckage.

For their families, those dates became the start of a silence that lasted lifetimes — years without answers, years of wondering if anyone still remembered. But in the past year, through a marriage of tenacious human effort and the quiet precision of modern science, both men have finally come home.

The Frozen Chosin

Clifton’s unit, the 31st Regimental Combat Team, fought in one of the Korean War’s most harrowing engagements — the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir. Surrounded by Chinese forces and battered by temperatures dropping to -30°F, many soldiers never made it out. For decades, Clifton was listed as Missing in Action.

In 2024, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) matched DNA from recovered remains to Clifton’s family. The science behind it — mitochondrial DNA analysis, cross-referenced with anthropological study — meant that even after 74 years, the frozen battlefield still had stories to tell.

When Clifton’s flag-draped casket arrived in Texas, it wasn’t just a military funeral. It was the final chapter of a family’s search.

The Long Flight Home

Yuen Hop’s story begins in the Bay Area, where he grew up the son of Chinese immigrants. In 1944, as a waist gunner on a B-17 Flying Fortress, he flew missions over occupied Europe. On November 21, his crew was assigned to bomb the industrial center of Merseburg, Germany — a target ringed by anti-aircraft guns.

The B-17 was hit. Witnesses saw it break apart near Bingen, Germany. Eight crew members were never identified; Hop was among them. His sister, then in her early teens, received the telegram that would define her family’s wartime memory.

Hop’s remains were buried in an American cemetery in Europe as “Unknown.” There they lay for nearly 80 years until DPAA historians began reviewing archival documents, German records, and wartime burial reports. The trail led them to remains that matched Hop’s age, build, and dental records. DNA testing with living relatives confirmed what the paper trail had suggested: Staff Sergeant Yuen Hop had been found.

In early 2025, his remains returned to California. His sister, now 93, met him at the airport.

The Science of Coming Home

Both Clifton’s and Hop’s returns are the result of patient, methodical work. The DPAA — operating out of laboratories in Hawaii and Nebraska — uses an arsenal of modern tools to identify the missing:

DNA Analysis — Especially mitochondrial DNA, which is passed down through the maternal line and can be matched with distant relatives.

Forensic Anthropology — Studying skeletal features to estimate age, stature, and other characteristics.

Dental Comparisons — Matching old dental charts with recovered remains.

Archival Research — Reconstructing combat events from unit diaries, maps, and foreign records to locate probable loss sites.

This blend of science and detective work means that even remains buried for decades — or scattered across crash sites — can still yield a name. Each case can take years, but the momentum is growing. DPAA now identifies over 200 service members annually, a number unthinkable in earlier decades.

Why It Matters

For the families, identification isn’t just a military formality — it’s an emotional release. As Clifton’s sister and Hop’s sister stood beside their caskets, both women were reclaiming something that had been suspended in time.

Closure doesn’t erase loss, but it transforms it. The “missing” status, with its endless questions, becomes a defined story. There’s a grave to visit, a place to lay flowers, a way to speak their names without the ache of uncertainty.

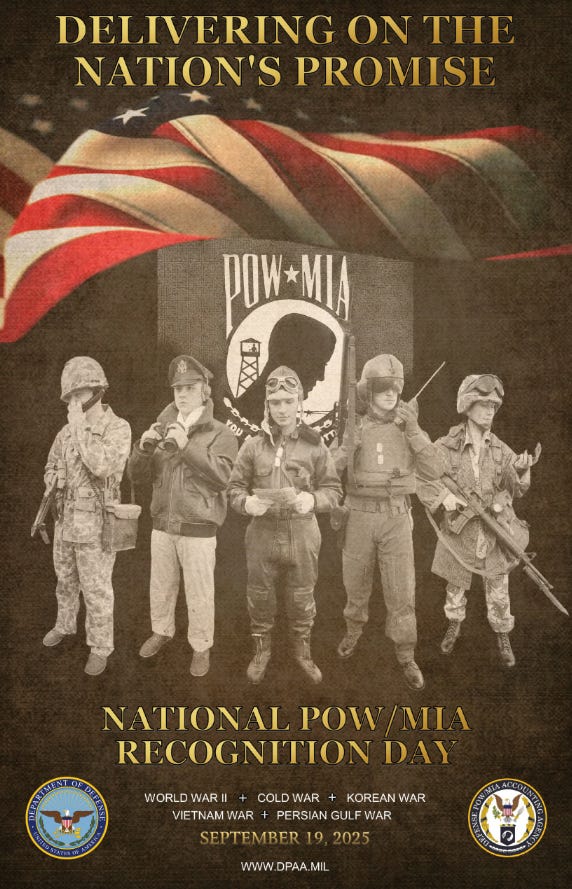

For the broader veteran community, these returns are reminders of a promise kept: You Are Not Forgotten. That phrase, printed on the black-and-white POW/MIA flag, is not just a slogan but an ongoing mission and a promise.

The Unfinished Work

There are still more than 81,000 Americans missing from past conflicts:

WWII: ~72,000

Korean War: ~7,500

Vietnam War: ~1,500

Cold War and later conflicts: smaller numbers, but still families waiting.

Each number represents not only a service member but a circle of loved ones who live with unanswered questions. Advances in DNA sequencing, international cooperation, and underwater recovery are steadily reducing those numbers — but the work will likely continue for generations.

Carrying the Story Forward

POW/MIA Recognition Day, observed this year on September 19, is a moment to honor those still unaccounted for and those who have finally come home. It’s also a chance to reflect on how remembrance is evolving.

In Clifton’s Texas hometown and Hop’s Bay Area neighborhood, their returns are already part of local memory — stories seen on local TV, passed in kitchens and community halls. The science may be new, but the welcome home is timeless.

As we look to the future, it’s worth remembering that these identifications aren’t just about the past. They are about reaffirming a national commitment: no matter how many decades have passed, no matter how far the search must go, we will not stop until every possible name is spoken, every family has an answer, and every hero is brought home.

If you visit the DPAA website, you’ll see a wall of case updates — names added, one by one. Each represents a journey like Clifton’s and Hop’s, from uncertainty into the light of homecoming.